EU General Court Annuls Council Sanctions Listing for the First Time on ...

For the first time in European sanctions practice, the Court explicitly held that the Council of the EU…

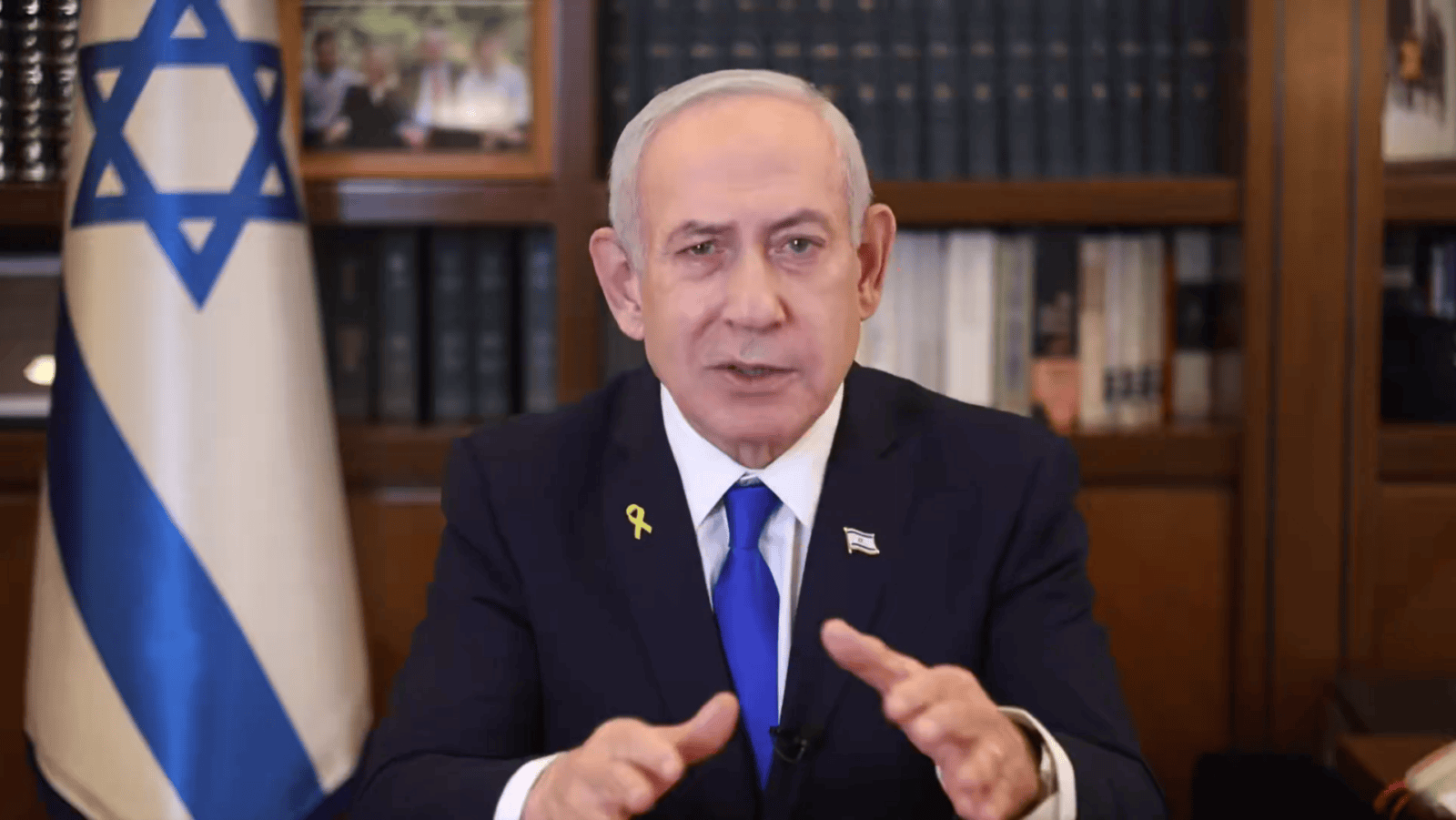

On November 30, 2025, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu submitted an unprecedented pardon request to President Itzhak Herzog in connection with his trial on charges of fraud, breach of trust, and bribery. This marks the first time in Israel’s history that a sitting prime minister has requested clemency before the conclusion of legal proceedings.

In the 14-page petition, Netanyahu does not admit guilt or express remorse. He justifies the request on grounds of “national interest,” claiming that continuing the trial harms the state and deepens societal divisions. The petition followed a letter from U.S. President Donald Trump to Herzog urging him to pardon the Israeli premier.

President Herzog called the request “an extraordinary appeal with serious ramifications” and stated he would consider it “responsibly and with utmost gravity.” The review process is expected to take several weeks.

Our partner, attorney Maxim Rakov, former legal advisor to Israel’s National Security Council, gave Radio REKA an extensive interview about the legal aspects of this unprecedented petition and the only precedent for pardoning high-ranking officials in Israel’s history.

There is indeed a precedent. In 1986, there was the famous Bus 300 incident, where Shin Bet leaders killed two terrorists after they had already been detained. Following a series of events, they received pardons because continuing and completing the criminal proceedings would have caused tremendous harm to the Shin Bet and the General Security Service.

Yes, that’s true. He ensured that the Shin Bet leaders, first, admitted to committing the offense, and second, resigned. Well, not entirely, let’s say. People left their positions, but some remained in the Shin Bet until the late 1990s. But yes, it was a requirement of the government’s legal department, particularly Yitzhak Zamir, that there be a police investigation, that they give testimony as part of that investigation, and request a pardon.

The president’s powers do exist, first of all. The president doesn’t make pardon decisions based solely on legal arguments. He has much broader authority. He can make decisions based on matters relating to the person requesting the pardon, based on broad state interests. So he can make a decision. The question is whether, from the Supreme Court’s perspective, the president’s decision would be valid.

You can appeal the legal validity of the president’s decision. That is, you can’t appeal against the president’s decision, because legally you can’t sue the president. But you can argue that the president’s actions are null and void—meaning the pardon he granted has no force. This is what they tried to do in 1986. The court rejected that petition and said that since the relevant conditions were met, the president’s decision was valid.

There was a situation where, back in 1986, a petition was filed with the High Court against the president’s decision. And the High Court upheld the president’s decision, saying that in that situation, under those conditions, the president could decide to grant a pardon, and it would be lawful.

Exactly. The court will look at what happened. First, let’s start with the fact that back then there was no indictment—there was a police investigation. The court said: even without an indictment, a police investigation is sufficient. The person who requested the pardon is a criminal, because this condition is written in the law on presidential powers—the president can pardon a criminal. So even though the person wasn’t convicted by a court, the very fact that there’s a police investigation and he requested a pardon—he’s already a criminal, and the president can pardon him.

There’s a serious problem. In this pardon request, the prime minister and his attorneys are saying: “I’m not a criminal, I didn’t do anything. But I’m requesting a pardon to serve higher public interests, so there won’t be discord in the country between different groups.” But he’s saying: “I’m not a criminal.” And the president cannot pardon someone who isn’t a criminal.

First, the president could say: “But he says he’s not a criminal. I’m legally not authorized to pardon a non-criminal.” The law states that the president has the right to pardon criminals. He doesn’t have the right to pardon those who are unlawfully prosecuted or wrongfully convicted. Unlike the American president, who can pardon anyone, including a turkey on Thanksgiving, who has absolutely unlimited powers, here it’s written in the law—pardon criminals.

There’s the first dilemma, and there also must be a process.

The president can grant a full pardon. In principle, nothing prevents the prime minister from continuing to perform his duties. And in principle, this appears throughout his request: “Grant me a pardon so I can continue fulfilling my duties without obstacles.” In other words, he’s not planning to resign.

The president could theoretically grant a conditional pardon, because under the law of legal interpretation, any powers include the authority to make a decision and impose conditions. Suppose the president says: “I’m granting a pardon on the condition that Benjamin Netanyahu resigns and doesn’t run as a candidate after his current term ends.” Theoretically, if he imposes such conditions and they’re not met, the pardon would be invalid. That’s also a question—will there be conditions for the pardon?

Furthermore: the president cannot sign a pardon unilaterally. The pardon must also be signed by the Justice Minister. Suppose the president signs a pardon and imposes conditions, but Justice Minister Yariv Levin disagrees with these conditions and refuses to sign…

Many possibilities—we’ll be following developments closely. Very interesting times ahead for us in the coming months.